Step off Oxford Street’s frantic thoroughfare and turn into Wigmore Street, and London’s tempo slackens. Georgian façades keep watch, bicycles glide past cafés, and conversations soften to neighbourly murmurs. In the middle of this collected scene stands Margaret Howell Marylebone, a store that whispers rather than shouts. Its oak floors, skylit ceiling and neatly folded shirts form a quiet manifesto of British craft, inviting shoppers to experience design that respects time rather than outruns it. This flagship is more than a shop: it is a working studio, gallery and local landmark. By analysing its origins, philosophy and architecture, we uncover how a single address has become a beacon for slow fashion in Marylebone and an anchor for London sustainable fashion seekers who value substance over spectacle.

Fun Fact: Until the mid-twentieth century, Wigmore Street echoed with piano scales; many leading instrument makers, including John Broadwood & Sons, kept workshops here, establishing a legacy of craftsmanship that still resonates today.

The Designer’s Path to Purposeful Fashion

Margaret Howell did not begin her career beneath runway spotlights. Fresh from a fine-art degree at Goldsmiths in 1969, she stitched papier-mâché beads in a Blackheath flat, sending the bolder pieces to Vogue. The magazine’s response was swift; Elizabeth Taylor ordered several designs, proving that global recognition can start at a kitchen table. Yet a different spark set her future course. At a jumble sale, Howell found a man’s pinstripe shirt sewn so precisely that every seam lay flat against the fabric. She unpicked the shirt, studied its architecture and realised good clothing could feel reassuring, functional and handsome all at once.

By 1976, she ran a workshop off South Molton Street backed by retail impresario Joseph Ettedgui. The clientele included women who borrowed their partners’ shirts and discovered Howell’s cuts suited them just as well. Each collection drew on working Britain rather than catwalk theatrics: fishermen’s guernseys, utility pockets, the relaxed drape of a gardener’s smock. Five decades later, critics still describe Howell as a “strong, quiet presence” a reputation earned not through celebrity endorsements but through patient, iterative craft that prizes wearability above novelty.

Philosophy of Lived-In Style and Quiet Luxury

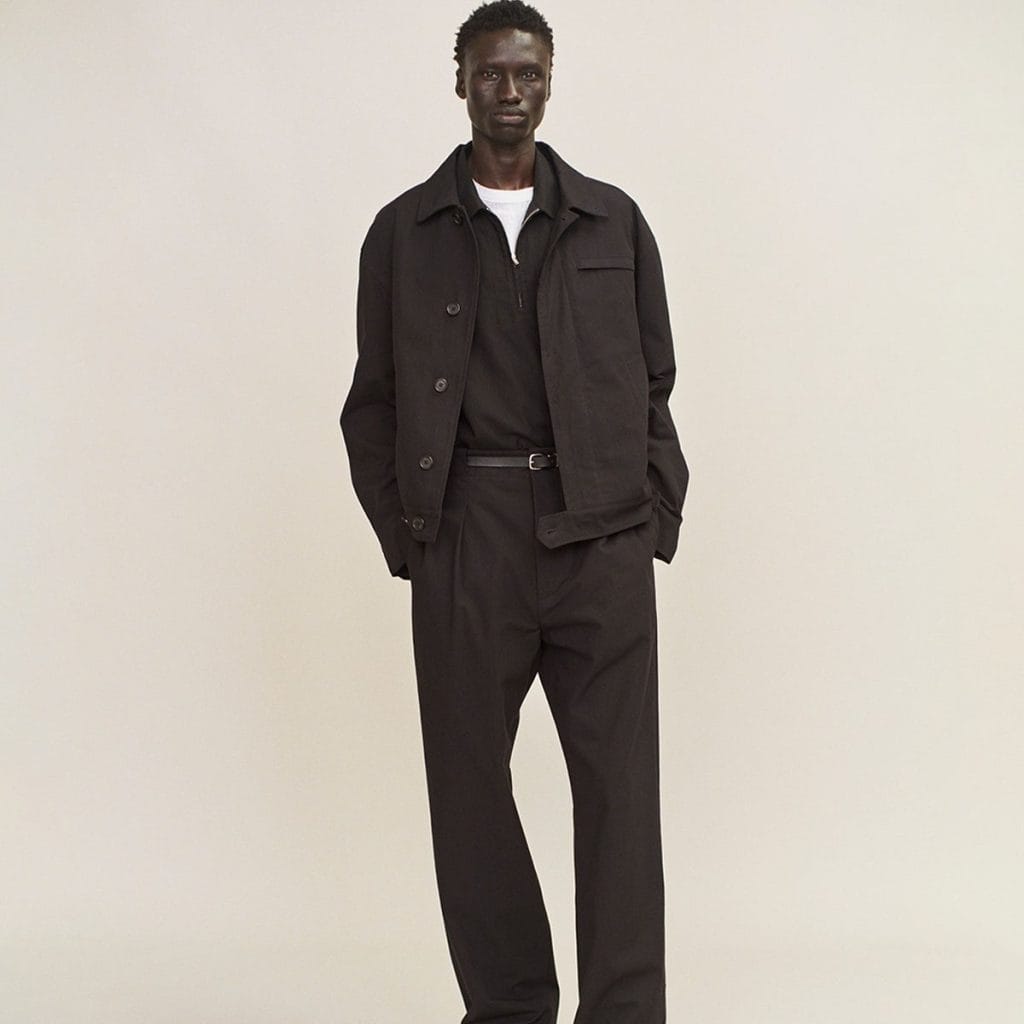

Luxury, in the Margaret Howell lexicon, is not gilded; it is functional, tactile and earned over years of use. She rejects seasonal gimmicks, explaining in interviews, “I design for real life.” Every shirt or coat must soften with washing, mould to the body and gain character with each crease. This principle reframes value away from exclusivity toward longevity. Where fast fashion chases the next micro-trend, Howell invites customers to curate wardrobes that mature alongside them.

The approach appeals to global shoppers disillusioned with churn. Japanese retailers adopted her work enthusiastically in the 1980s precisely because the pieces mirrored their own reverence for quality textiles and subtle detail. In London, Marylebone shopping enthusiasts treat her garments as investments, not impulses. Costly, yes, but the price is rationalised through enduring fabric, expert tailoring and versatile silhouettes that remain relevant year after year.

Materials, Craft and British Heritage

Stand in the flagship and run a hand across the rails: you will feel densely woven Harris tweed, crisp Italian poplin, Irish linen with visible slub, Scottish cashmere knitted on fully fashioned frames. Howell’s devotion to natural fibres is not marketing embellishment; it is a design constraint she refuses to abandon. She maintains long partnerships with mills and family-run factories, many within a short train ride of London. Raincoats are part-hand-cut at Mackintosh in Cumbernauld, while bench-made Derby shoes hail from a specialist workshop in Italy’s Marche region.

These choices are strategic as well as sentimental. Locally produced cloth allows tighter quality control and reduces transport emissions, aligning with modern expectations of responsible sourcing. Each garment’s label reads like a small geography lesson, rooting the piece in a network of skills that risk disappearing if designers chase cheaper alternatives abroad. When Howell speaks of “make,” she means the entire chain from farm to finish. This ethic underpins the store’s credibility and defends its prices.

Architecture That Mirrors the Brand

The Wigmore Street boutique opened in 2002 after Howell enlisted architect William Russell of Pentagram. Rather than impose theatrical fixtures, Russell uncovered the building’s hidden skylight. He expanded it, allowing natural light to wash over plywood floors and brushed-steel rails. Walls stay bare, colours muted; the products provide the palette. At the rear, open offices reveal pattern cutters drafting next season’s samples, dissolving the typical barrier between studio and shop. Visitors witness clothes in mid-development, underscoring Howell’s conviction that design is a working practice, not a glossy façade.

Furniture completes the narrative. Restored Ercol chairs sit beside folded knitwear; vintage Anglepoise lamps illuminate display tables; Robert Welch cutlery lines a shelf next to Japanese ceramic mugs. Each object is for sale, yet their presence also contextualises the clothes within a holistic domestic vision. Customers leave with the sense that dressing well is inseparable from living well.

Across Marylebone, the smaller MHL. Store on New Cavendish Street extends this ethos to a younger audience seeking utilitarian shapes at a slightly lower price point. Birch-ply shelving, retained parquet flooring, and simple signage echo the flagship yet assert a distinct energy. Together, the two locations map a complete brand universe within a five-minute walk, strengthening the district’s reputation as a nucleus of thoughtful retail.

Marylebone Village Synergy of Street and Store

Marylebone Village has spent three decades cultivating a walkable London neighbourhood where independent bookshops, pastry counters and niche design labels thrive side by side. Oversight by the Howard de Walden Estate means lettings are hand-picked rather than market-led, privileging character over chain ubiquity. The result is a commercial ecosystem that prizes provenance, craftsmanship and personable service: precisely the qualities central to Margaret Howell Marylebone. Customers who step out of the flagship often continue along Wigmore Street shopping for specialist eyewear at Cubitts, artisan fragrance at Perfumer H Marylebone, or rye loaves from Gail’s on George Street. Each purchase reinforces the neighbourhood’s identity, encouraging repeat footfall and nurturing loyalty that cannot be engineered by advertising alone.

Neighbours and Collaborative Ecosystem

Retail success here is collective. Howell’s minimalist windows reflect those at Studio Nicholson and Paul Smith, presenting a united front of understated British modernism. Nearby Trunk Clothiers sells Japanese denim and Scandinavian knits whose rigorous detailing echoes Howell’s own preoccupation with construction. At the same time, The Conran Shop Marylebone offers furniture that pairs naturally with the oak benches displayed inside the flagship. Shoppers move fluidly between these destinations, cross-pollinating brand stories and elevating average spend for every retailer. Local cafés, notably Monocle Café on Chiltern Street, benefit from the same clientele, proving that a high-quality fashion district can support coffee, culture and community in one continuous loop. Site managers track foot-traffic data to demonstrate that each design-led opening lifts total neighbourhood sales, an argument that strengthens future planning applications for independent operators.

Cultural Coordinates: Wallace Collection and Wigmore Hall

Marylebone’s cultural lattice deepens the shopping experience. Five minutes west, visitors reach the Wallace Collection, home to Fragonard’s The Swing, ordonnance silver and armour that gleams under eighteenth-century chandeliers. Two streets east, Wigmore Hall stages lunchtime recitals that routinely sell out. The schedule creates a rhythm: shoppers browse Howell’s knitwear, attend a Mozart quartet, pause for espresso and return for final fittings. Such adjacency matters because it places the brand within a continuum of British artistic achievement. A silk shirt designed on site feels conceptually closer to a hand-finished viol than to mass-produced fashion. The flagship’s periodic exhibitions on Lucienne Day textiles or Robert Welch cutlery reinforce this alignment, turning commercial floor space into a micro-museum that complements the grander institutions nearby.

The Customer Lens Praise and Critique

First-time visitors often remark on the store’s hush: no background playlist, no pushy up-selling, just the soft percussion of wooden hangers. Reviews cite the “gallery-like calm” and “faultless tailoring” as reasons for loyalty. Yet a contrary theme surfaces too. Several patrons describe staff who appear reserved to the point of aloofness, interpreting discretion as indifference. In hospitality training, Howell’s team is reminded that confidence need not eclipse warmth. Yet, execution can falter during busy Saturday trade. Price perception adds tension. A Donegal tweed coat priced above £900 invites scrutiny, particularly when MHL. Offers a field jacket for half that sum across the road. Savvier shoppers track seasonal reductions or visit the twice-yearly sample sale hosted in an upstairs studio, proof that even a premium label must engage with value-driven behaviour.

Sustainability Scorecard Philosophy versus Metrics

For decades, Howell has espoused the logic of buying fewer, better pieces, sourcing European cloth and minimising overproduction. By traditional standards, this earns an automatic place in the slow fashion London canon. Modern assessment, however, demands forensic transparency. Good On You’s “Not good enough” rating, published in July 2023, stems less from malpractice than from sparse public data: limited disclosure on living-wage compliance, chemical stewardship or biodiversity impact. The brand’s latest corporate report lists carbon targets and supplier audits, yet stops short of publishing factory addresses or wage brackets.

Industry watchers debate whether Howell’s implicit ethic should satisfy conscientious consumers. One camp argues that longevity itself curbs landfill and that measured growth supports skilled European factories—already a responsible position compared with ultra-fast fashion. The other camp insists that even heritage labels must quantify progress to retain trust. In response, Howell’s management has begun compiling supplier living-wage surveys and chemical inventories, a sign that quiet conviction will soon be paired with evidence. Until those figures surface, eco-minded shoppers may conduct their own due diligence, asking sales staff about fibre provenance or scanning QR codes on garment tags that trace production stages.

Actionable Guidance How to Shop Thoughtfully

Prospective visitors should plan mid-week mornings for an unhurried fitting when staff can explain the differences between brushed cotton and crisp poplin. Before arrival, browse the online “In Stock Now” filter, then use the flagship’s click-and-collect desk to secure limited sizes. For larger investments such as cashmere overcoats, ask about complimentary repressing and minor mending. These services extend each piece’s lifespan and embody the brand’s after-care philosophy.

Budget-conscious customers can begin with an MHL. Chalk-stripe work shirt or seasonal knit hat, both under £150 and produced to the same quality standards. The company’s partnership with resale platform Hardly Ever Worn It helps circulate pre-owned garments, lowering the cost of entry and reinforcing circular practice. Finally, pair your visit with nearby stops, perhaps Daylesford Organic Marylebone for lunch or Daunt Books Marylebone for travel writing, so the outing affirms the neighbourhood habit of conscious spending.

Quiet Design Lasting Influence

Margaret Howell Marylebone proves that a store can function as a studio, gallery and local touchstone without resorting to spectacle. By nurturing craft, maintaining European supply chains and placing authenticity above churn, the designer has secured a place in London fashion history that feels contemporary yet future-proof. Critics may question data gaps, but few dispute the garments’ integrity or the flagship’s role in sustaining timeless British menswear and womenswear ideals. As London retail pivots between digital convenience and experiential space, Wigmore Street offers a template for balance: light-filled rooms, attentive but unintrusive service, clothes that reward years of wear.

Still waters run deep.